It was initially discovered in 1862, but choline was officially recognized as an essential nutrient for human health by the Institute of Medicine in 1998.

This nutrient has numerous roles, including:

- Nervous system health, as it is vital for the creation of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter involved in healthy muscle, heart and memory performance

- Healthy fetal development, since it is required for a healthy vision, brain development, and proper neural tube closure, and its deficiency increases the risk of premature birth, low birth weight, and preeclampsia

- Healthy mitochondrial function

- Helping DNA synthesis

- Cell messaging, as it produces cell-messaging compounds

- Fat transport and metabolism, as it is required for the transfer of cholesterol from the liver

- Methylation reactions

- The synthesis of phospholipids, the most common of which is lecithin, which constitutes 40-50 percent of the cellular membranes and 70 — 95 percent of the phospholipids in lipoproteins and bile

Its increased intake has been linked to a lower risk of heart disease, breast cancer, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. It actually prevents the development of fatty liver by improving secretion of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles in the liver, required to safely transport fat out of it.

NAFLD is the most common form of liver disease in the U.S., and Chris Masterjohn, a Ph.D. in nutritional science, claims that choline deficiency is a more significant trigger of NAFLD than excess fructose. He claims that dietary fat and anything that the liver likes to turn into fat, such as fructose and ethanol, will promote fat accumulation of the body lacks choline.

Initially, the link between choline and fatty liver emerged from research into Type 1 diabetes, as studies in the 1930s found that lecithin in egg yolk (which is high in choline) could treat fatty liver disease in Type 1 diabetic dogs.

Masterjohn explains that choline is essential for the production of a phospholipid called phosphatidylcholine (PC), which is a critical component of the very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particle, which is required for the export of fats from the livers.

The amino acid methionine can act as a precursor to choline and can turn a different phospholipid called phosphatidylethanolamine directly into PC. Thus, the combined deficiency of choline and methionine will drastically lower the ability to package up the fats in the liver and to send them out into the bloodstream.

Therefore, the lover needs choline to eliminate excess fat, and the more dietary fat we consume, regardless of its type, the more choline we need.

Masterjohn adds that the most significant culprit in NAFLD is excessive fructose, as all of it must be metabolized by the liver and is primarily turned into body fat as opposed to being used for energy.

He says that researchers in 1949 demonstrated that sucrose and ethanol had equal potential to cause fatty liver and the resulting inflammatory damage and that increases in dietary protein, extra methionine, and extra choline could prevent these effects.

Yet, while carbohydrates, healthy saturated fats, and unhealthy PUFA-rich oils can lead to the accumulation of fat in the liver, lipid peroxidation, and associated inflammation is primarily driven by PUFA-rich oils like corn oil. Corn oil promotes inflammation by raising vulnerability to lipid peroxidation due to its total PUFA content and by lowering tissue levels of DHA due to its high omega-6-to-omega-3 ratio.

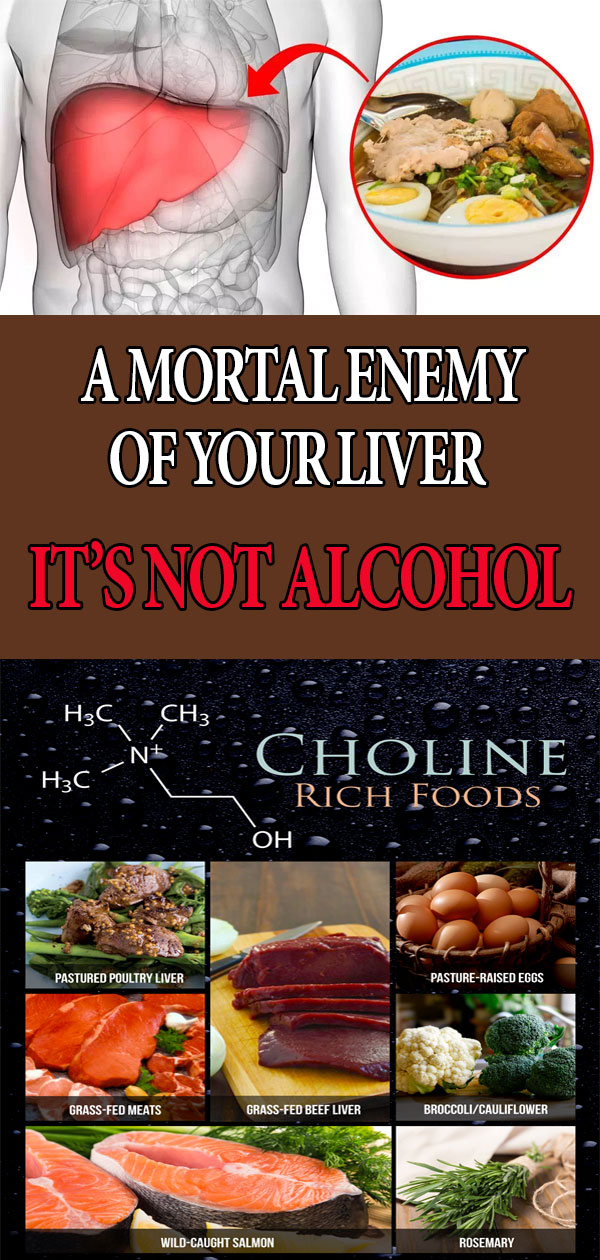

When it comes to the dietary sources of choline, eggs are definitely one of the best ones. A single hard-boiled egg can contain about 113 milligrams (mg) to 147 mg of choline, or about 25 percent of the daily requirement. Yet note that this is the egg yolks only, while the whites only contain traces of this micronutrient.

Yet, a 100-gram serving of grass-fed beef liver has 430 mg of choline. Other sources include krill oil, wild-caught Alaskan salmon, organic pastured chicken, shitake mushrooms, cauliflower, asparagus, and broccoli. Take a look at the following chart of other dietary choline sources:

|

Food |

Milligrams |

Percent |

|

Beef top round, separable lean only, braised, 3 ounces |

117 |

21 |

|

Soybeans, roasted, ½ cup |

107 |

19 |

|

Chicken breast, roasted, 3 ounces |

72 |

13 |

|

Beef, ground, 93% lean meat, broiled, 3 ounces |

72 |

13 |

|

Fish, cod, Atlantic, cooked, dry heat, 3 ounces |

71 |

13 |

|

Mushrooms, shiitake, cooked, ½ cup pieces |

58 |

11 |

|

Potatoes, red, baked, flesh and skin, 1 large potato |

57 |

10 |

|

Wheat germ, toasted, 1 ounce |

51 |

9 |

|

Beans, kidney, canned, ½ cup |

45 |

8 |

|

Quinoa, cooked, 1 cup |

43 |

8 |

|

Milk, 1% fat, 1 cup |

43 |

8 |

|

Yogurt, vanilla, nonfat, 1 cup |

38 |

7 |

|

Brussels sprouts, boiled, ½ cup |

32 |

6 |

|

Broccoli, chopped, boiled, drained, ½ cup |

31 |

6 |

|

Cottage cheese, nonfat, 1 cup |

26 |

5 |

|

Fish, tuna, white, canned in water, drained in solids, 3 ounces |

25 |

5 |

|

Peanuts, dry roasted, ¼ cup |

24 |

4 |

|

Cauliflower, 1” pieces, boiled, drained, ½ cup |

24 |

4 |

|

Peas, green, boiled, ½ cup |

24 |

4 |

|

Sunflower seeds, oil roasted, ¼ cup |

19 |

3 |

|

Rice, brown, long-grain, cooked, 1 cup |

19 |

3 |

|

Bread, pita, whole wheat, 1 large (6½ inch diameter) |

17 |

3 |

|

Cabbage, boiled, ½ cup |

15 |

3 |

|

Tangerine (mandarin orange), sections, ½ cup |

10 |

2 |

|

Beans, snap, raw, ½ cup |

8 |

1 |

|

Kiwifruit, raw, ½ cup sliced |

7 |

1 |

|

Carrots, raw, chopped, ½ cup |

6 |

1 |

|

Apples, raw, with skin, quartered or chopped, ½ cup |

2 |

0 |

Choline is also available in dietary supplements containing choline only, in combination with B-complex vitamins, and in some multivitamin/multimineral products.

In most dietary supplements, the amounts of choline range from 10 mg to 250 mg. The forms of choline in these supplements include choline bitartrate, phosphatidylcholine, and lecithin.

According to the Institute of Medicine, the “adequate daily intake” value for women is 425 mg, 550 mg for men and 250 mg for children.

Yet, note that the requirements can vary depending on age, diet, genetics, and ethnicity.

Studies have also shown that men with organ dysfunction need a higher daily intake, as well as postmenopausal women, pregnant and breastfeeding women, athletes, and people who eat a diet rich in saturated fats.